I got onto the G30 highway heading east towards Urumqi, the regional capital and the nexus point for all the roads in Northern Xinjiang. The highway hugs the foothills of the formidable Tian Shan Mountains heading east and west, all the way to the Alashankou land port with Kazakhstan. The road to the east was clear in the afternoon sunshine, and I was cautiously optimistic that I could reach my objective for the day, the town of Fuyun. Nestled in the Altai mountains, the settlement sits to the south of the jagged seam where Russia, China, Kazakhstan and Mongolia come together. This was to be my launchpad for the border crossing, which in my mind loomed like a massive sinister unknown. I had fears of phantom bureaucratic hurdles springing up on my arrival, vines of red tape snarling me to some dusty shack in the desert, forbidden to cross over for some inscrutable yet very Chinese reason.

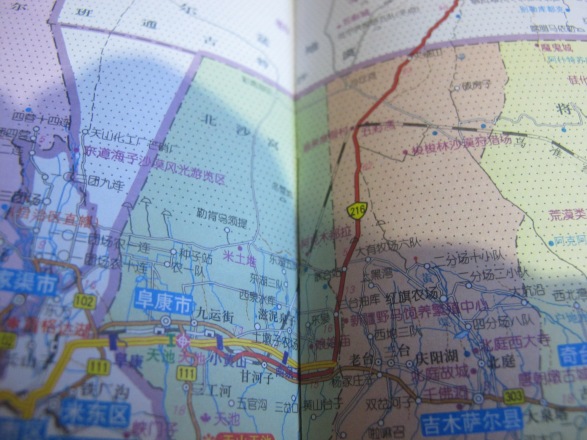

I made decent progress through the afternoon, despite a brief stop to replace a bolt on a support strut that had terrifyingly come loose while at speed. At the outskirts of Urumqi I turned north onto the 216 national highway, which would take me through the heart of the Gurbantünggüt Desert, home to the furthest point on land away from any ocean, over 1600 miles.

North of Urumqi some nasty bumper to bumper traffic congealed, grinding my progress to a crawl for almost an hour. This, combined with the now boiling intensity of the sun, began to dehydrate me rapidly as I was wrapped in layers of highly-protective-yet-not-very-breathable leather and canvas. Traffic on a motorcycle is annoying, consisting of waddling awkwardly among plodding cars. When I was not quick enough to move forward the usual ten feet or so the eager driver behind would honk incessantly until I picked up the slack. My right boot was getting so hot from the sun and the idling engine that I began to worry its rubber sole might actually melt into the asphalt. I could not wait to get off these big faceless arteries and onto the more local routes, where traffic might mean a few sheep or the odd camel.

Once I passed a highway interchange the traffic mercifully cleared, and I pulled back on the throttle to speed up and let the wind cool me off, weaving gleefully between the lines to celebrate my return to open space. Exhausted from the heat, I stopped in a town on the outskirts of the desert called Fukang. I needed to retie my now sagging luggage, buy a funnel for fuel, and get some food. The town was another Han chinese grid of bright and hopeful concrete tower blocks, streetlights laced with the usual alien-looking neon strip lighting, and a small yet bustling core of urban activity: shoppers examining racks of clothing in the warm evening air to the thump of house music blaring from nearby speakers. These towns seem very strange when entering from the surrounding scrub. In America we rarely see such distinct geographic margins. Towns have ballooned out into the suburbs, and when approaching you enter an urban gradient, as developments, strip malls and movie theaters pop up with increasing frequency the closer you get. Here there was a discrete margin at which the buildings stopped and the desert began. To be in the center of these small cities felt bizarre, as if all this activity was somehow contrived, irrelevant when considered in the context of the vast empty expanse beyond the little urban cluster.

After asking a local for a recommendation, I was led to a restaurant just off one of Fukang’s main avenues. I ordered the regional staple Banmian/laghman: thick hand-drawn noodles topped with a spicy stew of meat and vegetables. While slurping it down I looked at the map in dismay; there was no way I could make it to Fuyun, another 600 Km north with nothing but desert in between. My itinerary had been overly ambitious, and the process of reconciling my idealized itinerary with reality would become a daily routine. I decided to compromise, settling for Wu Cai Wan (five colored hills) which was a more reasonable 200 clicks up the road. The town is named for the layers of bright colored sediment that have been exposed by the gouging desert winds.

I headed out of town around 8:30 PM back onto the 216. I was warned by some locals who helped me load my bike to avoid the road after sundown. Apparently after dark trucks from coal mines that dot the region clogged the highways, carrying their sooty cargo down to the population centers and freight hubs, making for rather dangerous driving conditions. Already having compromised my itinerary once, I was determined to make more progress, so I shrugged off their advice to delay and set out.

Route 216 heads east towards Jimsar, before striking north into the Gurbantünggüt Desert towards the Altai region

As I struck out north into the desert the sun dipped below the western horizon. True to the locals’ words large red lorries began to fill the previously empty road, wheezing and cranking their heavy loads at high speeds, and soon I was sandwiched in the midst of the massive line of them. The one behind me was no more than 15 feet away, and when the harsh gusts of wind ripped across from the desert I could see chunks of coal fly off the truck ahead of me. The cargo was poorly secured with tarps, and I feared getting beamed in the face with a lump that would take me down and trample me under the convoy. At one point I looked up and noticed the characters on the back of a truck in front of me: “contains highly corrosive material”, at which point imagines of me rear-ending the truck and slowly dissolving into a tidy puddle by the roadside filled my head. I slowed way down, and I began to regret my decision to push on.

Thankfully after a nerve-wracking hour the ant-line of trucks took a turn to the left, chugging west towards a presumable mine. The road cleared and soon I was alone again. As I continued north into the desert the light faded quickly, and the winds picked up to a roar, pressing the collar of my jacket onto my throat like it was out to choke me. Around me the landscape shifted from a flat scrubland to a series of rolling hills, resembling sandy beachside dunes. I found myself having to stop repeatedly to take a break from the wind. Signs going by warned of the wildlife crossing the roads in the area, a designated nature preserve which included populations of wild bactrian camels.

I didn’t see a thing in the darkness, and soon the wind had chilled me to the bone. As the temperature continued dropping I longingly imagined a hotel room and hot shower waiting for me. The fatigue of the first day’s ride, at this point approaching 10 hours, was taking its toll.

Fortunately I soon saw the telltale neon lights on the horizon that indicated hotels and the small outpost of Wu Cai Wan. I pulled in wearily and unloaded my gear by the cheapest looking one and checked in. I was shocked to see the volume of dust that streamed out when I got in the shower, just from a single day’s ride. I tried to take down some notes but fell asleep within minutes, completely exhausted. I’d make it a paltry 350 km, barely half my goal for the day. Yet despite this, my spirits were still undimmed, perhaps naively. My barely legible half-conscious notes read, “I definitely feel like I can do this now. I’ve already dealt with so many hurdles to get here, so what’s a few more!”